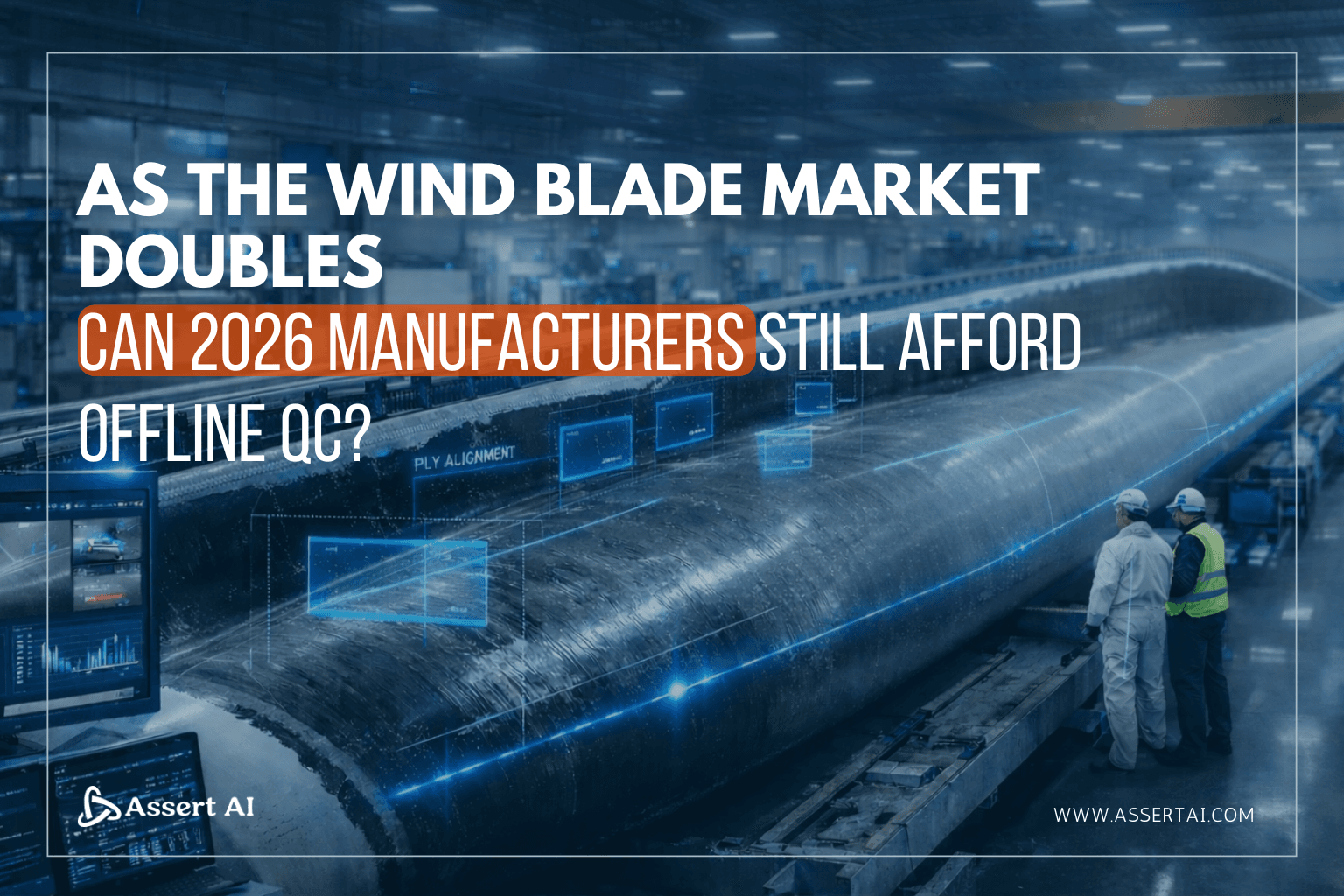

A Factory Pushed to Its Limits

Step into a modern wind turbine blade manufacturing facility and one reality is immediately clear: the margin for error has collapsed.

Blades now approach and exceed 100 meters in length. Composite layups involve dense stacks of carbon and glass fiber, engineered to millimeter-level tolerances. Cycle times are shrinking under aggressive delivery commitments tied to long-term renewable energy contracts.

In this environment, composite manufacturing quality control is no longer a downstream activity. It is a core production constraint.

Yet in many plants, one critical assumption remains unchanged.

Most quality decisions are still made after the process is complete.

Offline inspections. Manual visual checks. Sampling-based audits. Photos reviewed hours or days later.

This approach worked when blades were shorter, volumes were lower, and defect risk was localized. But modern wind turbine blade manufacturing has fundamentally changed the equation. Composite architectures are more complex, load paths are less forgiving, and the cost of a single defect can escalate into weeks of rework, scrappage, or long-term warranty exposure.

The contradiction shaping the industry’s next phase is increasingly difficult to ignore:

- Wind energy demand is accelerating

- Blade production capacity is scaling rapidly

- Yet quality systems remain largely reactive

Manufacturers are being asked to build larger, faster, and cheaper while tolerances tighten and margins compress. Under these conditions, reliance on offline inspection exposes structural limitations in traditional composite manufacturing quality control models.

The question facing the industry is no longer whether advanced technologies will influence quality at some point in the future. It is far more immediate:

As the wind blade market scales exponentially, can manufacturers still afford to “find and fix later”? Or does the absence of true in-process quality control become an operational risk by 2026?

Why Quality Risk Is Compounding, Not Stabilizing

The macro forces reshaping the industry are well understood. Global wind capacity additions continue at record pace. Blade designs are growing longer, heavier, and structurally more demanding. Certification scrutiny is intensifying, while plants expand faster than skilled labor pools can realistically grow.

What is often underestimated is how these forces interact.

Why Quality Risk Is Compounding

The macro forces reshaping wind blade manufacturing are well understood but their implications for quality are often underestimated.

The Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) reports that ~127 GW of new wind capacity was installed globally in 2024 alone, one of the highest annual installation volumes on record. Each gigawatt represents thousands of large composite blades entering production pipelines worldwide.

Several trends are converging simultaneously:

- Blade length escalation: Standard designs have moved from ~70 meters to 100 meters and beyond, amplifying bending moments and fatigue sensitivity.

- Composite complexity: Higher carbon fiber content, thicker root sections, hybrid materials, and more intricate ply sequences.

- OEM scrutiny: Tighter certification standards, traceability requirements, and documentation expectations.

- Capacity pressure: Rapid plant expansions often outpace skilled labor availability.

At the same time, according to Fortune Business Insights, the global wind turbine blade market that was valued at $27.55 billion in 2023, reached approximately $30.17 billion in 2024, and is projected to exceed $200 billion by 2032. This is not incremental growth. It is structural expansion.

And scale changes everything. It does not increase quality risk linearly. It multiplies it.

As blades grow longer, bending moments increase and fatigue sensitivity tightens. As composite architectures become more complex, the tolerance for execution variability shrinks. As cycle times accelerate, the opportunity to pause, inspect, and correct diminishes.

In this environment, composite manufacturing quality control becomes a defining operational challenge.

A small deviation that once affected a manageable area can now compromise an entire structural section. A resin imperfection that might have been repairable early becomes deeply embedded after curing and consolidation.

Yet many quality systems are still optimized for post-process discovery rather than in-process quality control.

The Hidden Cost of “Find and Fix Later”

Offline quality control has an intuitive appeal. Complete the process, inspect the outcome, and repair what’s wrong. But in composite-intensive wind turbine blade manufacturing, this logic carries hidden and escalating costs.

By the time defects are detected, full value has already been added.

Material has been consumed. Labor is sunk. Cycle time is spent. Downstream schedules are already committed.

Rework at this stage is invasive and disruptive. Inspection queues grow longer. Work-in-progress accumulates. Scrap risk rises sharply. And when defects escape detection entirely, warranty exposure shifts the cost far beyond the factory floor.

This is why offline QC is no longer a safety net.

It has become a silent margin drain in modern quality control in wind energy operations.

Why 2026 Is an Inflection Point

Several structural pressures converge around 2026 that make legacy quality models increasingly untenable.

- Production capacity is expanding faster than experienced labor availability

- Product assembly duration need shrinking to meet contractual delivery commitments

- OEMs are demanding auditable, process-level quality evidence

- Insurance and liability scrutiny around structural failures is intensifying

- Margins are tightening under commoditization pressure

Under these conditions, inspection-heavy quality systems struggle to keep pace.

You cannot inspect quality into a process that moves too fast to stop.

And you cannot afford to discover defects only after they are irreversibly embedded.

This is why 2026 represents an inflection point rather than a gradual transition.

From Outcome Inspection to In-Process Assurance

Leading manufacturers are already shifting their mindset.

The core question is no longer, “Is the blade acceptable at the end?”

It is, “Is the process behaving correctly right now?”

This shift moves quality upstream, embedding verification directly into critical manufacturing stages rather than deferring judgment to the finish line.

During ply layup, in-process quality control validates fiber orientation, overlap, and sequencing before additional layers compound the error. Real-time confirmation of layer count and distribution prevents late-stage structural compromises that are costly to reverse.

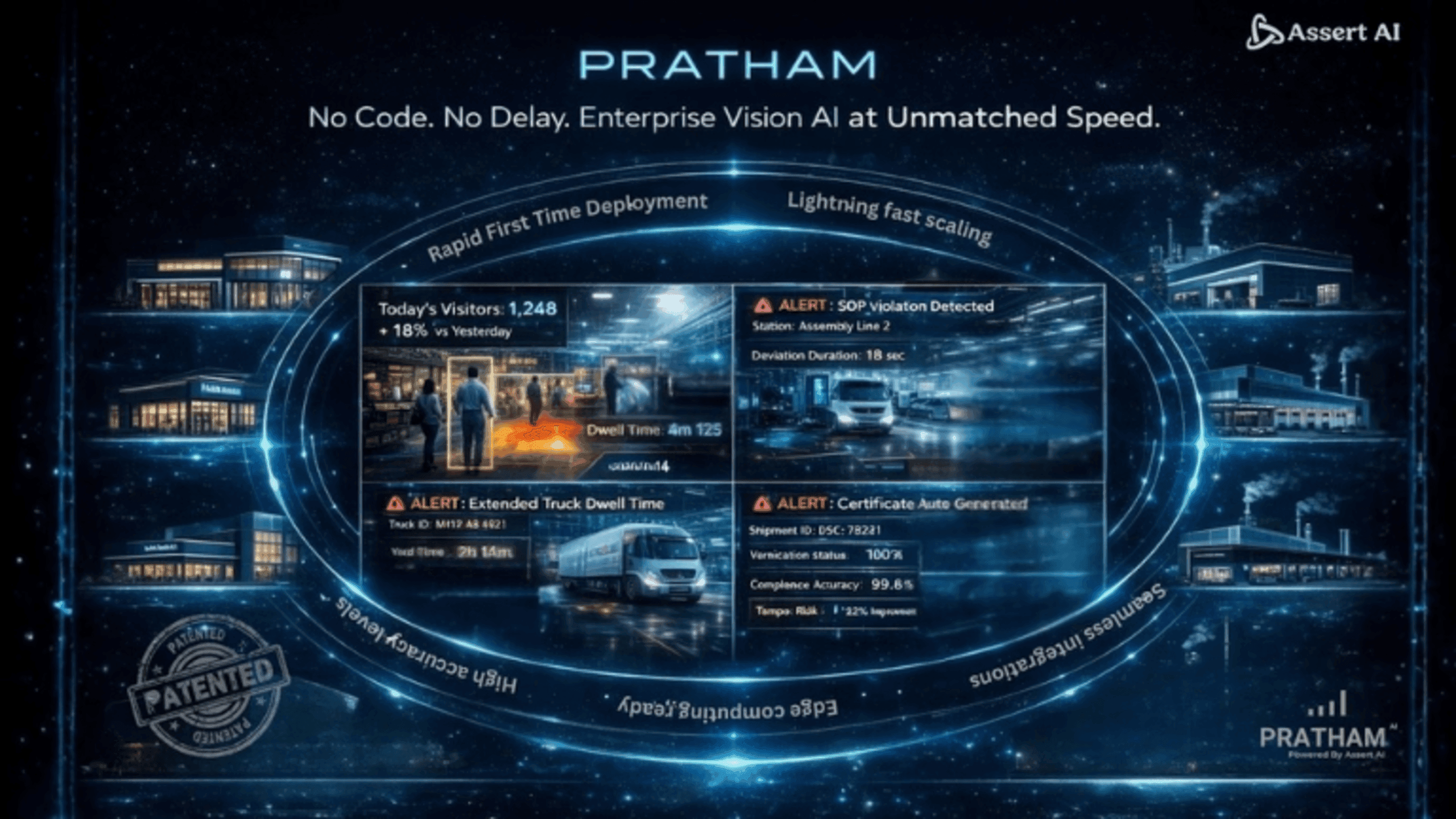

During resin infusion, AI-driven vision systems actively monitor resin flow in real time and interface with PLC-controlled valves to regulate when infusion starts, how much resin is delivered, and when flow is stopped. By adjusting valve timing and flow rates as the process unfolds, the system prevents under-infusion, over-saturation, and premature completion before defects become embedded.

By detecting SOP deviations in real time and acting before defects form, manufacturers shift quality from post-process inspection to true prevention- where control, not correction, defines execution.

When Detection Is Not Enough: Insight Must Drive Control

As processes accelerate, detection alone has diminishing value if it cannot influence execution.

This is where computer vision quality inspection becomes transformative.

When real-time visual inspection data feeds directly into statistical process control systems, isolated defect signals turn into early indicators of process drift. Instead of logging failures after the fact, manufacturers gain visibility into trends while corrective action is still low-cost and localized.

When inspection intelligence is further connected to production control systems, quality becomes enforceable. Layup steps can be paused, resin infusion parameters adjusted, and curing delayed until deviations are resolved.

Importantly, this does not remove human operators from the loop. It elevates them with contextual, actionable intelligence at the moment it matters most.

What Wind Manufacturing Leaders Should Expect in 2026

By 2026, the divide between leaders and laggards will be increasingly visible.

Leaders will:

Move quality control in wind energy upstream into every critical step

Treat quality as a real-time control variable, not a downstream checkpoint

Design plants assuming minimal tolerance for rework

Adopt scalable computer vision quality inspection aligned with process control

Others will continue to firefight- absorbing higher scrap rates, longer inspection cycles, and growing warranty exposure.

The difference will not be access to technology. It will be how deeply quality is embedded into the operating logic of wind turbine blade manufacturing itself.

The Strategic Question

The wind blade market will grow. Policy signals may fluctuate, but long-term capacity expansion across onshore and offshore markets remains intact.

The real question is who captures value and who absorbs risk as complexity rises.

In a multi-billion-dollar industry, quality can no longer be something you inspect at the end of the line. It must be engineered into the process, enforced in real time, and proven continuously.

By 2026, manufacturers will not be judged by how many blades they produce, but by how consistently they produce them right the first time.

And in the next phase of wind manufacturing, prevention is not an advantage. It is the only scalable strategy.